The Story of the House

In about 950 AD, King Edgar granted to the Abbey of Our Lady & St. Ethelburga at Barking lands at Yenge-atte-Stone (whence we get the modern name of Ingatestone). As one of the principal manors held by the nuns of Barking, it subsequently also became known as Gynge Abbes. In 1535, Henry VIII ordered his Chief Secretary, Thomas Cromwell, to put in train the process that was to lead to the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Cromwell's Proctor or assistant, a young lawyer from Devon called William Petre, had the job of visiting the monastic houses of Southern England to draw up a record of their possessions and to persuade them to surrender to the King.

Among the abbeys he visited was that of Barking and he was immediately attracted by its manor of Ynge-atte-Stone and took a lease of the property. One of the attractions was, no doubt, its Latinised name - Ginge ad Petram - which made it sound as though it had belonged to the family for centuries. In 1539, the lands of Barking Abbey having been surrendered to the Crown, Dr. Petre purchased the manor for its full market price of £849 12s 6d. This transaction, together with the purchases and grants of other former monastic lands, could well have been construed as the plundering of Church property but a Bull of Confirmation issued by Pope Paul IV exonerates Petre from any such charge and absolves him from the Interdict of Excommunication imposed on Henry VIII provided that he endowed an almshouse foundation for the poor. The almshouses he accordingly founded may still be seen (though not on their original site) in Ingatestone High Street.

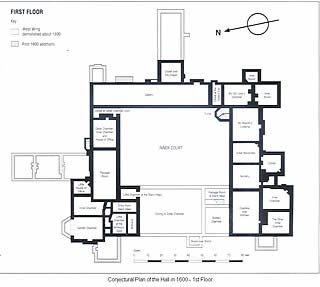

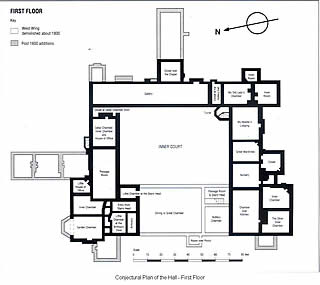

Petre considered the old steward's house at Ingatestone "scarce mete for a fermor to dwell on" and so he demolished it, building instead, on the same site, the house we substantially see today - "very fair, large and stately, made of brick and embattl'd". This house was in the form of a hollow square and, thanks to Petre's contacts with the monasteries, for whom all the most able architects worked, of very advanced design for the time. It is one of the very earliest domestic buildings to have had a piped water supply and flushing drains, fed from springs which continued to supply the house until only about ten years ago. Nevertheless, it was hardly modern plumbing by today's standards; in Thomas Larke's 1566 survey of the house, all the main bedrooms contain a "little room within" equipped with a "close stool".

When William Petre died, his widow, continued to reside at Ingatestone Hall and so his son, John, bought Thorndon Hall, near Brentwood, which, for the next 300 years or so, was to become the principal family seat. Ingatestone Hall remained in the family and was used as a holiday retreat or a residence for the dowager or married heir. However, the ninth Lord Petre, for one, took up more permanent residence at the Hall during the six year period (1764-1770) during which the grandiose new Thorndon Hall was being built to a Palladian design by James Paine. Possibly, therefore, it was he who was responsible for alterations to the house carried out around this time: a new wing was added to the existing north wing and the buildings around the outer court were rebuilt, complete with the one-handed clock above the arch.

Soon after the ninth Lord moved back to Thorndon, the west wing, which housed the Great Hall and Dining Chamber, was demolished (to leave the U-shaped plan we see today) and the rest of the house "modernised", with many of the mullioned casements replaced by sash windows and the internal layout changed to give rooms of a more convenient size and provide for passage-ways, a feature unknown in earlier houses where one room leads directly into the next. These alterations also included the subdivision of the house into four separate apartments. Two of these, in the North Wing, were reserved for family retainers.

In 1876, the bulk of Thorndon Hall was destroyed by fire but it was in 1919, following the death of the 16th Lord Petre in the Great War, that the family moved back to Ingatestone. Lady Rasch, the 16th Lord's widow, immediately set about restoring the house to its original Tudor appearance and layout. It was a mammoth task.

Not only was the house somewhat dilapidated but it was also disfigured by a large number of ill-considered and poorly executed alterations and small extensions which had been carried out to facilitate its subdivision into apartments. The builders who replaced the old brick-mullioned casements with timber sashes overlooked the significance of the supporting function of the mullions and the lintels had begun to sag badly. Under Lady Rasch's close supervision, with retired architect, W.T. Wood as Clerk of the Works, the local building firm of F. J. French set about removing these accretions, replacing anything irretrievably lost with reproduction work of the highest quality. Only close inspection, for example, reveals the difference between the "new" mullioned windows on the ground floor of the central west façade from the original ones in the Gallery above. The first phase of these works was completed in 1922. A masque to celebrate their completion was performed in the Gallery, in which the eight-year-old Lord Petre played his ancestor, Sir William, with his younger sister as Cupid. Further extensive works were carried out in the mid-thirties.

Following the Second World War, during which the house was used by the girls of Wanstead School, it soon became apparent that the days of keeping a house of this size fully staffed and utilised were past and so, in the 1950s, the North wing was let to Essex County Council for use by the Record Office. This arrangement continued until the end of the 1970s and, during this time, many thousands of Essex schoolchildren visited the annual exhibitions that were mounted there.